Although Charles Christopher Godden (1876-1906) was only 30 years old when he died, and had spent just 5 years on the mission field of Ambae, Vanuatu,[1] his untimely and violent death in 1906 has been greatly used by God to spread the good news of peace among the local inhabitants. His story and legacy are remembered today, even after Ambae was rendered uninhabitable by a volcanic eruption in 2018.

Although Charles Christopher Godden (1876-1906) was only 30 years old when he died, and had spent just 5 years on the mission field of Ambae, Vanuatu,[1] his untimely and violent death in 1906 has been greatly used by God to spread the good news of peace among the local inhabitants. His story and legacy are remembered today, even after Ambae was rendered uninhabitable by a volcanic eruption in 2018.

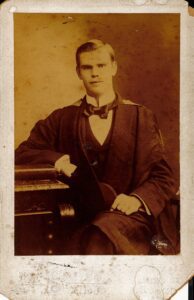

Charles Godden was born and raised on a farm in country Victoria. The minister at Euroa, Rev William Hancock, invited Charles to confirmation classes. Embracing wholeheartedly the faith that was taught, Charles not only requested confirmation but asked Hancock shortly afterwards about becoming a clergyman. Despite having to work on the farm, Charles studied at night under the tutelage of Rev Charles Barnes, Vicar of Yea. In only 2 years, he had mastered Greek and Latin. This prepared him for theological studies at Perry Hall, Bendigo, under Rev Nathaniel Jones. In 1895, Charles wrote to his sister Louisa “God has been very gracious to me thus far…My constant prayer is that I may further his cause.”[2] When Jones was appointed Principal of Moore College, he was able to bring Charles with him and support him in his studies. After his ordination in 1899, Charles worked as a curate at St Michael’s Surry Hills, alongside the Rector Dr James Manning. His abilities and servant-hearted attitude greatly impressed Dr Manning, who reported that Charles was so generous that he gave all his clothes away to poor parishioners![3]

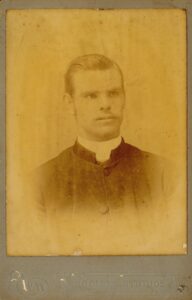

The same zeal for the gospel which had led Charlie from his confirmation class into the ministry was then used by the Spirit to spur him on into mission work. The Bishop of Melanesia, Cecil Wilson, had been working hard recruiting people for the Melanesian Mission. Bishop Wilson visited St Michael’s in 1900 and spoke of the need for mission workers in the South Pacific. Charlie volunteered straight away, was posted to Ambae as the first missionary to that island in 10 years, and established a mission headquarters at Lolowai Bay.[4] In a letter to Rev Hancock, he wrote, “There have already been six martyrs … I shall therefore have the opportunity of glorifying God by my devotedness to the lost sheep whom the Good Shepherd is seeking.”[5] The linguistic proficiency which allowed him to master Greek and Latin so quickly was put to use in learning the local Havai language and commencing translation of the New Testament. His reports to the Mission show the challenges of his work. In 1903, he reported that there was frequent violence between villagers.[6] He intermediated in a village feud that had resulted in several murders, even though he knew he might be shot.

Godden’s work on Ambae took place in the context of colonial possession and exploitation in the wider Pacific region. The infamous practice of ‘blackbirding’—forcing or tricking Pacific Island men into slave-like labour conditions on the Queensland cane fields—had only just ceased. Many of the labourers were returning to their homes, including one named Alamemea. He had suffered brutal treatment, and when he retaliated by striking an overseer, was imprisoned and forced to stand neck deep in water. Upon his release and return to Ambae, he vowed revenge on Europeans and swore to kill the next white man he saw.

In October 1906, the family of Moses Warilawau, who had become a Christian and built a church in his village, asked Charles to come and perform some baptisms, including for a sick child. The locals warned Charles not to go, because they knew of Alamemea’s threat. Such was Charles’ dedication that he went regardless. When Alamemea saw him returning from the baptisms, he struck Charles with an axe. Seeing the injuries, local chief Roroi vowed to hunt down the perpetrator but was stopped by Charles, who said, “No, I come down here in peace, I will die in peace.” He was carried down to the shore and onto a boat to take him back to Lolowai Bay. Just before he died, he made a last appeal for peace: “Let there be no fighting because of me. Let there be peace.”[7]

In October 1906, the family of Moses Warilawau, who had become a Christian and built a church in his village, asked Charles to come and perform some baptisms, including for a sick child. The locals warned Charles not to go, because they knew of Alamemea’s threat. Such was Charles’ dedication that he went regardless. When Alamemea saw him returning from the baptisms, he struck Charles with an axe. Seeing the injuries, local chief Roroi vowed to hunt down the perpetrator but was stopped by Charles, who said, “No, I come down here in peace, I will die in peace.” He was carried down to the shore and onto a boat to take him back to Lolowai Bay. Just before he died, he made a last appeal for peace: “Let there be no fighting because of me. Let there be peace.”[7]

Alamemea’s brothers were ashamed of the crime he had committed and helped hand him over to the authorities so that he could be taken to Fiji for trial. They also gave Chief Roroi a pig for slaughter during the traditional reconciliation service that took place shortly afterwards. When Chief Roroi died, the local people buried their weapons in his grave.[8]

In tribute, Principal Jones wrote of Godden, “he was…unselfish and thoughtful. I…always felt he could be depended upon for tasks other men would be unwilling to undertake.”[9] His death and his pleas for peace were used by God in the spread of the gospel among the local people, who continued to honour Charles’ memory. On the 50th anniversary of his death, a memorial plaque was unveiled in Moore College’s Cash Chapel as “a constant reminder to students of the price which has been paid for the evangelization of the world.”[10] Centenary commemorations were planned for 2006 but disrupted by volcanic activity, and took place in 2007, with Archbishop of Sydney Peter Jensen in attendance. He was presented with a ceremonial spear as a mark of sorrow and respect. Godden’s initial work on translating the New Testament into Havai was continued by Bible Society Australia and Bible Society of the South Pacific, and published in 2013 in Godden’s memory. The Psalms tell us that the death of God’s faithful servants is precious in His sight (Ps 116:15), and the life and sacrificial death of Charles Godden has resulted in a legacy of faithfulness to God among the people of Ambae.

Erin G. Mollenhauer works in Library and Archives at the Donald Robinson Library of Moore College

[1] Before independence in 1980, Vanuatu was known as New Hebrides. The island of Ambae is referred to in older sources as Opa, Omba or Aoba.

[2] Quoted in Ruth Godden, Lolowai: the story of Charles Godden and the Western Pacific, (Sydney: Wentworth Press, 1967), 22.

[3] Godden, Lolowai, 32.

[4] Hilliard, David. God’s Gentlemen: a history of the Melanesian Mission, 1849-1942 (St Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1978), 182.

[5] Quoted in John Harris, “Forgotten and remembered: the martyrdom of Charles Christopher Godden” St Mark’s Review 229 (Sep 2014): 62.

[6] Godden, Lolowai, 229.

[7] Harris, ‘Forgotten and remembered,’ 70.

[8] Harris, ‘Forgotten and remembered,’ 71.

[9] Godden, Lolowai, 246.

[10] Sydney Diocesan Magazine (Oct-Nov 1956), 37.