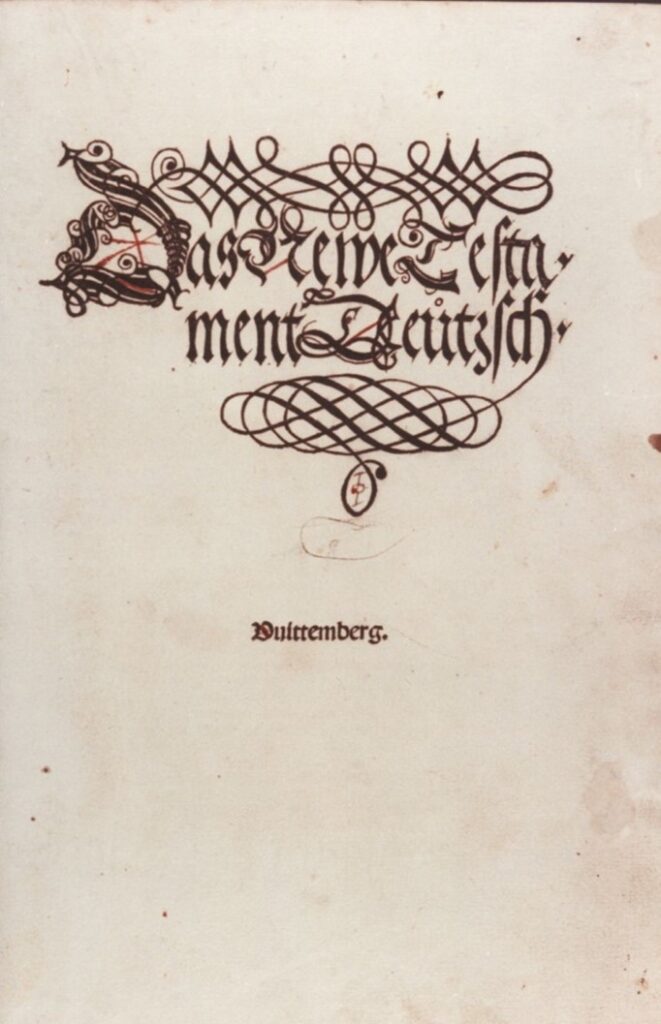

500 years ago today, on 21 September 1522, one of the landmark moments of the Protestant Reformation took place, one that is not often celebrated as much as the posting of the 95 theses, Luther’s stand at the Diet of Worms in April 1521, or the formal “Protest” submitted to the Diet of Speyer in April 1529. On that day the first copies of Martin Luther’s German translation of the New Testament emerged from Melchior Lotther the Younger’s print shop in Wittenberg. Luther had started working on it while he was in protective custody in Frederick the Wise’s fortress outside of Eisenach, the Wartburg. Astonishingly, he finished a rough first draft in just eleven weeks! After being urged to undertake the task by his colleague Philip Melanchthon, Luther had first mentioned his intention to begin to his friend Johannes Lang on 18 December 1521 and he brought a completed draft with him when he returned to Wittenberg on 6 March 1522. It was, as one biographer puts it, a “masterful linguistic and theological achievement”.[1] It was a translation from the Greek text, rather than from the Latin Vulgate. It was a translation into the dialect used most extensively in Germany, the dialect used in the Saxon court of the Wettin family, the Meissner Kanzleisprache.[2] Precisely because it was published in September 1522, it is sometimes known as the Septembertestament. The first print run is estimated to have been between 3,000 and 5,000 copies and it sold out within a few weeks. A revised edition appeared in December with a number of corrections.

In translating the New Testament, Luther made use of the critical edition of the Greek New Testament produced by Erasmus in 1516. He was aware of Lorenzo Valla’s Notes on the New Testament from a Collection of Greek Copies, which had identified a number of translation errors in the Vulgate. While that important work was most likely first published in the 1440s, it was Erasmus who drew it to the attention of scholars when he republished it in 1505. This serious engagement with the Greek text is what made Luther’s translation such a landmark publication. There had been a variety of German translations of the Bible, or parts of it, prior to Luther.[3] However, as Melanchthon observed, they were invariably taken from the Vulgate and were often of poor quality. Even the best of them, such as the Mentelin Bible of 1466, were written in a German far removed from everyday use and for that reason were difficult to understand. Luther’s linguistic and general literary skill would produce something much more useful and truer to the original text, and that is why Melanchthon pushed Luther to do it. After all, what else would he do while couped up in his “kingdom of the birds”, as Luther referred to the Wartburg? Luther’s would be the first of the great vernacular Bibles that would be characteristic of the Reformation.[4] It would be a large part of the inspiration for William Tyndale of England (he also had the earlier example of John Wycliffe) and Pierre Olivétan of France (who was also influenced by his teacher, the humanist Jacques Lefèvre). The Catholic theologian Jerome Emser even produced a revision of Luther’s New Testament for use by German Catholics in 1527.

Luther was committed to making the Scriptures accessible to ordinary people. This is how they would grasp the gospel and be freed from the chains of Roman religion. So he determined to use ordinary German. In 1530, reflecting on the ongoing process, by then undertaken by a translation team and no longer by Luther alone, and which led to the publication of the whole Bible in German in 1534, Luther explained, “we must inquire about this of the mother in the home, the children on the street, the common man in the marketplace. We must be guided by their language, the way they speak, and do our translating accordingly. That way they will understand it and recognize that we are speaking German to them.”[5] The ordinary use of the German language would influence Luther’s translation. But the relationship was reciprocal. Luther’s translation was to have a very significant impact on the German language, not dissimilar to the way Tyndale’s translation, and later the King James Version, impacted the English language. Luther’s employment of “forceful words, succinct expressions and simple declarative sentences” contributed to the appeal of the translation as did the use he made of well-known German folk songs and common proverbs. His translation shows a particular sensitivity to questions of rhythm and style.[6] He chose to express the meaning of the Greek text in a common and easily readable German idiom, rather than in a literal word for word translation.

That is what led to the one of the great attacks upon Luther’s translation, surrounding his translation of Romans 3:28. The ESV translates this verse as, “For we hold that one is justified by faith apart from works of the Law”. A literal rendering of Luther’s German would be “We therefore conclude that a person is justified without the works of the Law, only through faith”. Luther’s opponents seized on the addition of the word “only”. Was the man who stood before the world declaring his conscience was bound to the word of God now adding to it? Luther insisted he “knew very well that the word solum [“alone”] is not in the Greek or Latin text”. Yet he defended his translation on the basis that it conveyed the sense of the text, it was necessary if the translation was to be clear and vigorous, and it is a common German idiom to convey a stark contrast, such as Pauls’ contrast of works of the Law and faith, to use “not” (or “without” in the rendering I have made) and then “only”.[7]

A remarkable feature of Luther’s translation was the prefaces he prepared for each book of the New Testament. This was not a new thing — Jerome had provided prefaces to each biblical book in his Latin translation, the Vulgate — but Luther’s prefaces were vehicles for Protestant theology anchored in the biblical text. Most famous of these is his Preface to the Epistle to the Romans, which eventually took on a life all of its own. John Wesley spoke of the radical impact hearing it read publicly had made on his own life. The best known passage from that preface (present in the published edition of 1522) is this:

O it is a living, busy, active, mighty thing, this faith. It is impossible for it not to be doing good works incessantly. It does not ask whether good works are to be done, but before the question is asked, it has already done them, and is constantly doing them. Whoever does not do such works, however, is an unbeliever. He gropes and looks around for faith and good works, but knows neither what faith is nor what good works are. Yet he talks and talks, with many words, about faith and good works.

Faith is a living, daring confidence in God’s grace, so sure and certain that the believer would stake his life on it a thousand times. This knowledge of and confidence in God’s grace makes men glad and bold and happy in dealing with God and with all his creatures. And this is the work which the Holy Spirit performs in faith. Because of it, without compulsion, a person is ready and glad to do good to everyone, to serve everyone, to suffer everything, out of love and praise to God who has shown him this grace. Thus it is impossible to separate works from faith, quite as impossible as to separate heat and light from fire.[8]

Today the availability of the Bible in our own language is taken for granted by many of us, though we must acknowledge that there are still thousands of language groups who do not have their own translations of the Bible. The written word of God is available to us to read, to study, to memorise, to lead us to confession and to praise. Luther played a very significant role in that becoming the norm for so many of us. The Septembertestament was not perfect (no translation ever is) but it was a landmark and the anniversary of its appearance is something worth celebrating.

[1] Martin Brecht, Martin Luther: Shaping and Defining the Reformation 1521–1532 (1986; trans. J. L. Schaaf; Minneapolis: Fortress, 1990), 49.

[2] Eric W. Gritsch, “Martin Luther as a Bible Translator”, in Donald K. McKim (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Martin Luther (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 71.

[3] Christoph Burger reports that there had been 18 High German and 4 Low German translations produced between 1466 and 1522. Christoph Burger, “Luther’s Thought Took Shape in Translation of Scripture and Hymns”, in Robert Kolb, Irene Dingel & L’ubomír Batka (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Martin Luther’s Theology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 481.

[4] Heinz Bluhm, “The Literary Quality of Luther’s Septembertestament”, PLMA 81/5 (Oct. 1966): 327.

[5] Martin Luther, “On Translating: An Open Letter”, in E. Theodore Bachmann (ed.), Luther’s Works (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1960), 35:189.

[6] Heinz Bluhm, Luther Translator of Paul: Studies in Romans and Galatians (New York: Lang, 1984), 405.

[7] Luther, “On Translating”, 188–189.

[8] Martin Luther, “Preface to the Epistle of Paul to the Romans”, in E. Theodore Bachmann (ed.), Luther’s Works (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1960), 35:370–371.