How do you build a theological library in a new colony? For William Grant Broughton, Archdeacon of NSW and then Bishop of Australia, the answer was crowdsourcing!

The commercial book trade in Australia has only existed from the 1830s onwards, with William McGarvie at the Australian Stationery Warehouse (which also operated a circulating library from 1829), and James & Samuel Tegg who opened a bookshop in George St in 1835[1].

Broughton arrived in Australia in 1829 on the convict ship John, and one of his chief concerns was recruiting and equipping clergy. Throughout the 1830s he worked steadily on establishing a library of books to support their work. He spent the years 1834-1835 in England, and during this time he promoted the need to resource the growing Australian church.

One of Broughton’s friends, and correspondent over many years, was Rev. Edward Coleridge. He worked as Vicar of St Margaret’s, Mapledurham (near Reading), and as a Master at Eton College. During the 1830s, he launched an appeal urging people to donate books for the clergy in Australia. This appeal was made known among the colleges of Oxford and Cambridge, and elicited a response that was both generous and indicative of the church politics of the time.

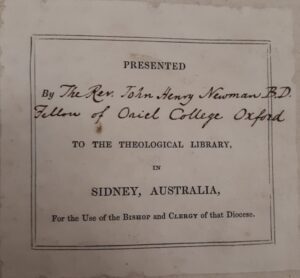

Broughton can be theologically situated towards the High Church end of the Anglican spectrum[2], and his letters to Coleridge show a keen interest in the development of the Oxford Movement. Coleridge himself was a friend of the leaders of the Oxford Movement John Henry Newman and Edward Pusey[3]. Several donations of books came from both these men – Newman, then a Fellow of Oriel College, Oxford, later a Roman Catholic Cardinal, gave a 3-volume set of the works of St Jerome, printed in 1674. Pusey donated an 1838 edition of the Confessions of St Augustine.

The Early Church Fathers feature prominently in this collection. A major donor was the President of Magdalen College, Oxford, Rev Martin Routh, whose contributions included a 1569 edition of the Works of St Augustine. William Palmer, Fellow & Tutor at Magdalen College, donated a 1690 edition of the works of Bernard of Clairvaux, as well as a set of the Tractarians’ namesake work Tracts for the Times.

The Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (also known at the time as ‘Dr Bray’s Associates’) donated a collection of books which included Henry Hammond’s Practical Catechism (1677) and John Tillotson’s Of sincerity and constancy in the faith (1695). This evangelistic society had been formed by Dr Thomas Bray in 1698, and the distribution and publication of Christian books through schools and libraries was one of their main activities. In 1809, the Associates of Dr Bray had given a donation of books to the colonial chaplain Samuel Marsden (some of these books also form part of our collection).

A bookplate was printed specifically for these donations, so that the donor’s name could be recorded. It features the curious spelling ‘Sidney’. This might be an understandable error, as although the city of Sydney was named after Baron (later Viscount) Sydney, earlier Barons used the variant spelling.

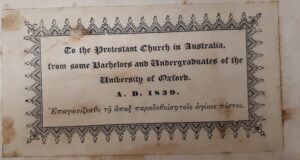

On the other hand, Evangelical students at Oxford were also generous donors of books, preferring to remain anonymous under the collective name of ‘Bachelors and Undergraduates’. Their donation in 1839 of over 50 books shows distinctly Reformed tastes, with works by Luther, Calvin, Richard Baxter and “A preservative against Popery” by Edmund Gibson. The bookplate which identifies these donations includes a quote in Greek from Jude 3: Contend for the faith which was once delivered unto the saints.

This process of acquiring books was an ongoing project for Broughton in the 1830s. In 1837, he writes to Coleridge that [the library] is now, even with the contributions which I obtained for it in England, beggarly in the extreme. Books of reference or authority we have scarcely any; and in the rampant attitude which our Roman Catholic and dissenting brethren have assumed, we are reduced oftentimes to unpleasant straits from the want of all authentic information, except what our own private stores of books or memory may supply.[4]

Two years later, he was delighted with the arrival of more books: I have the gratification of acknowledging the arrival of 5 chests, the unpacking of which has afforded me satisfaction unspeakable. It gratifies me day by day, and many times every day, to look at the fine old fellows standing in long array; and to think what treasures of wisdom are thus secured to the present and future dwellers in this land; many of whom I hope will have more leisure than falls to my lot to read and inwardly digest the contents of these Volumes… Whenever you see the inside of a library pray think of ours; and congratulate yourself on the opportunity, ability and inclination with which you have been blessed to do this eminent service to learning and religion.[5]

And again in 1840:

Among the efforts which you have made, I can account none more well-timed or more important to the improvement of the present and future generations here than the supply of Books … any man who shall make himself master of the contents even of the books we can now produce, will not be contemptible either as a scholar or a divine.[6]

This collection became part of the Sydney Diocesan Library, which operated out of Church House until its closure in the 1950’s when the collection was transferred to Moore College Library.

Bishop Broughton was keenly aware of the importance of having accessible resources to support theological education and ministry. This remains the mission of the Donald Robinson Library.

Tax-deductible donations supporting the work of the Library can be made on the Library Fund page.